Lidwina: Years 1-4

Just like every superhero (and villain) has an origin story, every person with a chronic illness has a diagnosis tale. Sometimes they are long, painful, and wrought with missteps before the final verdict. Sometimes they are abrupt and definitive. I fall into the second category of my grossly over-generalized scale. I had a weird symptom, saw my general practitioner, was sent to a neurologist, had an MRI, and then I had Multiple Sclerosis.

While I had heard of M.S., I was absolutely ignorant of what it was. I had never met anyone with this particular brand of disease. I did what any normal 21st century academic would do and searched the internet. Then, I was terrified. The list of ways this disease, if untreated and even sometimes treated, can wreak havoc on the body is long and scary. In the tumult, I did find three words to cling to: chronic not fatal. I will deal with this for the rest of my life, but it probably will not kill me.

The work in the series “Lidwina” is not intended to be an education about the disease itself. That information is easily accessible at the library. Instead, it is a visual representation of the things I think about since my diagnosis. The things I obsesses about.

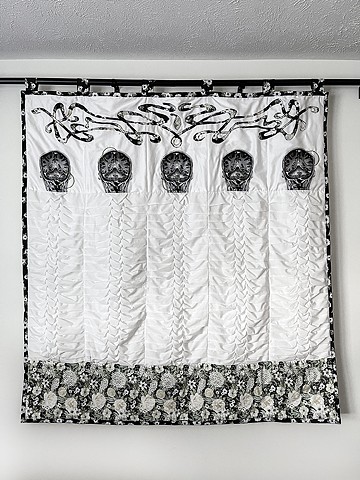

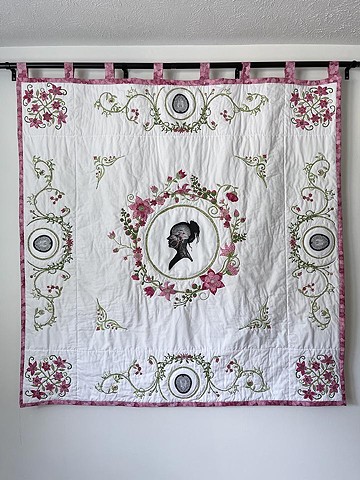

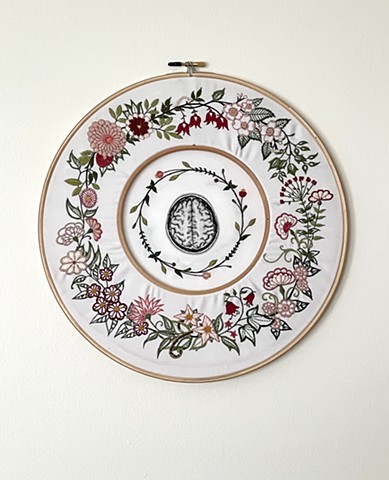

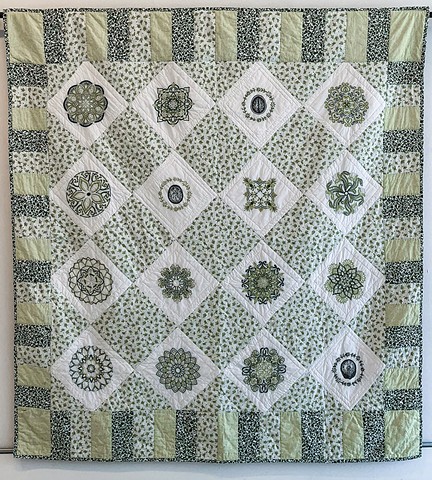

Until a few years ago my art practice was exclusively photographic in nature. Even my hobbies of quilting and embroidery were born from the stacks of fabric I had accumulated as backdrop material. It was not until after my first appointment with my MS specialist did I ever seriously consider combining photographic imagery and fabric. The appointment was to review my MRI and discuss treatment options. I was equally excited and terrified. Of course, the prospect of learning precisely how sick I was frightened me. But, as a photographer, I was thrilled at seeing real pictures of MY brain. I left that appointment disappointed. My disease was not mild and my brain was visually…unexceptional. My neurologist was wonderfully kind, informative, and knowledgeable. He recommended starting treatment immediately with the strongest medicine available. In retrospect, I don’t know what I was expecting from my MRI images. At the very least I wanted to recognize my brain as my own. It is my command center. It stores everything that makes me uniquely me. I wanted it to be special. After some research and a lot of trial and error I successfully printed one of my MRI images onto fabric using my photographic inkjet printer. If my brain was not visually special on its own, I was going to make it special by embroidering flowers around it.

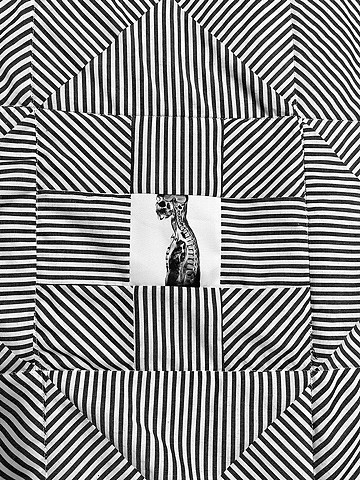

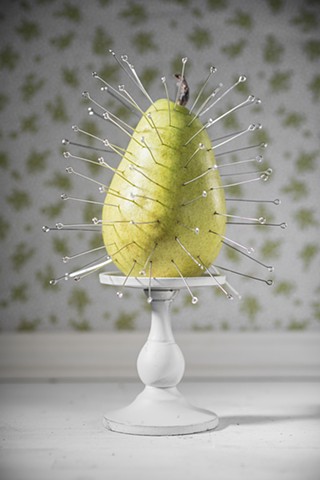

I still make art that is exclusively photographic and I still make quilts and embroidery as a hobby, but now I also make pieces that combine the skills from both pursuits. The language imbedded in the ordinary act of sewing is a comfort. The repetition and domesticity of it is a type of meditation and fear-inoculation. Looking at and handling my MRI images while crafting them into something that could be used for warmth or decoration saps some drama from the stark medical documents. The more I manipulate them into something else the less scary they are. The language imbedded in the constructed photograph lets me explore my thoughts, feelings, and reactions more metaphorically. The un-reality depicted mimics my mental landscape trying to reconcile my disease with my everyday life after it was upended with a single diagnosis. Typically, doctors cannot match the location of lesions on the brain to specific symptoms. The 13 most recent images of flowers blooming in impossible places represent the lesions that “lit up” with the contrast injection on my first MRI. The flowers are paired with places on my body where my disease has been revealed in numbness, fatigue, insomnia, concentration, and coordination. The images are still and quiet with an anxious held-breath wariness the same way I have to approach the unpredictability of relapse.